RCEI Affiliate Focus on Katherine Bermingham, Associate Professor, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences

By Jacqueline Stromberg

Over 4.5 billion years ago, Earth formed through elemental and celestial processes whose chemical and isotopic signatures remain preserved in Earth and space rocks. Some of these ancient materials originate from nearby planetary bodies and fall to Earth as meteorites. For Dr. Katherine Bermingham, Associate Professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, studying these fragments of space began with curiosity and continues to be fueled by her resilience, a quality that powers Bermingham’s scientific journey from the unknown through to discovery.

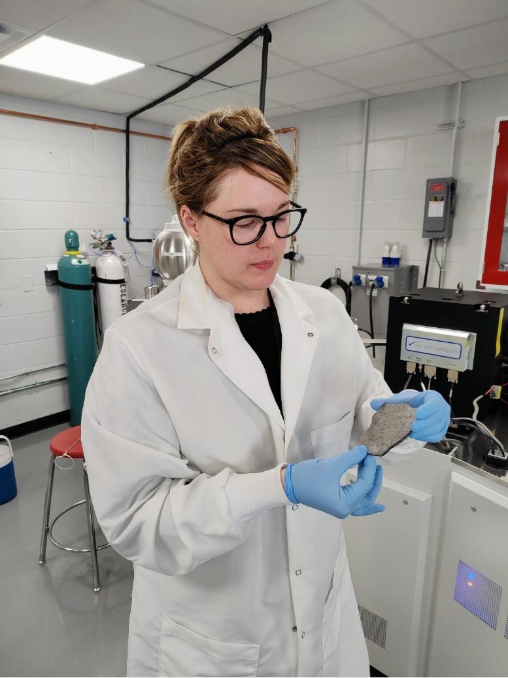

Bermingham is a cosmo-geochemist who studies the chemical makeup of meteorites to learn the story of Earth’s formation and the Solar System. She leads the Isotope Cosmo-Geochemistry Laboratory, where she uses isotopic analysis of meteorites and Earth rocks to study the formation and evolution of the Solar System and Earth. Her research also extends to the characteristics of other terrestrial planets, such as core composition, water origin, and geological history. Through isotopic analysis, the slightest difference in various rock signatures can reveal the fundamental processes that shaped the Solar System and Earth over billions of years.

Credit: Katherine Bermingham.

While Bermingham primarily works with siderophile (iron-loving) elements and their isotopes to understand planetary formation, she notes the role isotopes play in climate science. “Isotopes are so cool in terms of climate change. Because of research involving isotopes, people can detect where increasing greenhouse gases are coming from,” she says. Carbon isotopes, for example, are used to distinguish emissions from fossil fuels versus natural sources, providing proof of human-caused influence.

Bermingham brought a state-of-the-art Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometer (TIMS) to Rutgers. This instrument enables high precision isotopic analysis, specifically of siderophile elements, which help scientists better understand the formation of Earth and the Solar System. Designed by Nu Instruments, Bermingham worked with the company to optimize this TIMS for siderophile analyses. Even the smallest sample analyzed by TIMS can reveal vital details about Earth’s geology. The ability to unlock hidden stories found in the isotopic analyses reflects the deep scientific curiosity that drives her work. “This TIMS is one of a kind, it’s brand new to Rutgers… it is a thrill, to be able to learn every day and be able to teach people new things; that keeps curiosity alive,” she noted.

Bermingham’s passion for how things worked began in her home country of Australia. She attended the Australian National University, where she graduated with a Bachelor of Science (with Honors). During her studies, she took a class taught by the late Professor Ross Taylor, a pioneering planetary scientist, who ignited her passion for chemistry and space exploration.

She approaches meteorite research with adaptability, finding scientific value in both successful discoveries and unexpected outcomes. Meteorite samples come from museums, dealers, and through hands-on fieldwork. While working with the Desert Fireball Network (DFN), Bermingham found a piece of the Moon (Lynch 002) in the Nullarbor Plain in Australia, spotting something that might have been mistaken for an ordinary rock or animal droppings, but isotopic analysis confirmed it to be a fragment from the Moon. However, not all expeditions lead to such findings. During a different trip with the DFN, she was part of a team that followed a projected meteor trajectory through the intense terrain of the bushland in Queensland, Australia. After searching and finding no physical evidence of the meteor, they concluded that the meteor had likely dispersed into a fine powder from a sonic boom and rained down in the area.

Bermingham is driven by her positive approach to her work and life in general. In response to a question about overcoming challenges, she responded, “I don’t know anyone who doesn’t have challenges or change constantly thrown at them in one form or another. I think being curious and flexible in your expectations forms the basis of resiliency.

At Rutgers, Bermingham is not only expanding the research of Earth’s planetary systems but also promoting a culture of scientific curiosity, perseverance, and resilience. Her work with the impressive TIMS machine, traveling through remote areas of Australia, and sharing her findings, reminds us that even the smallest of fragments can tell a story.

Jacqueline Stromberg is an Office of Climate Action Intern, majoring in Environmental Policy, Institutions, and Behavior, within the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences.