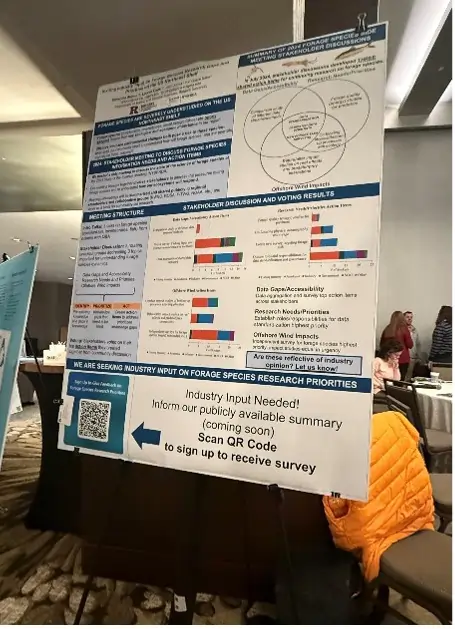

Student Support Program

About the Student Support Program

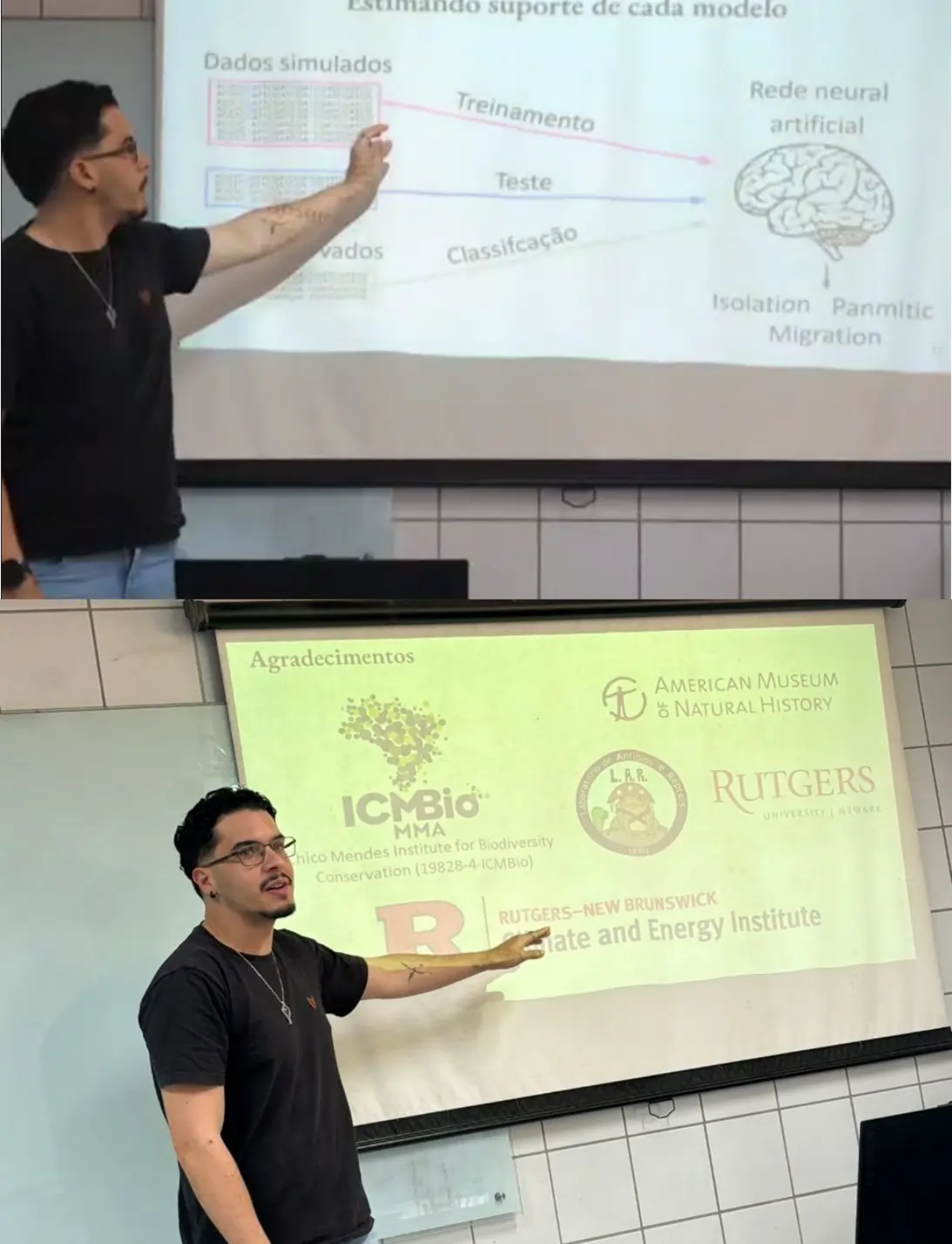

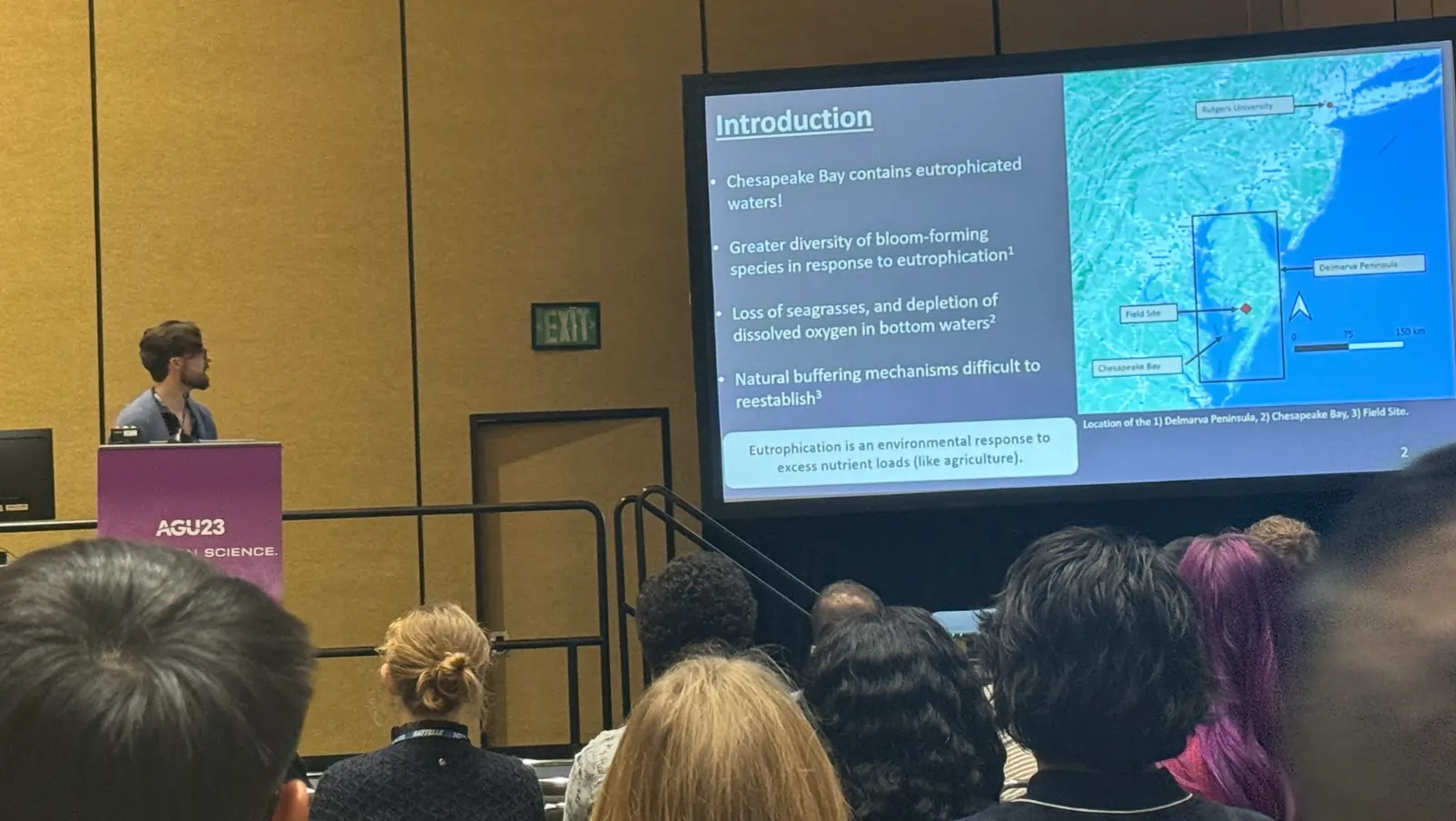

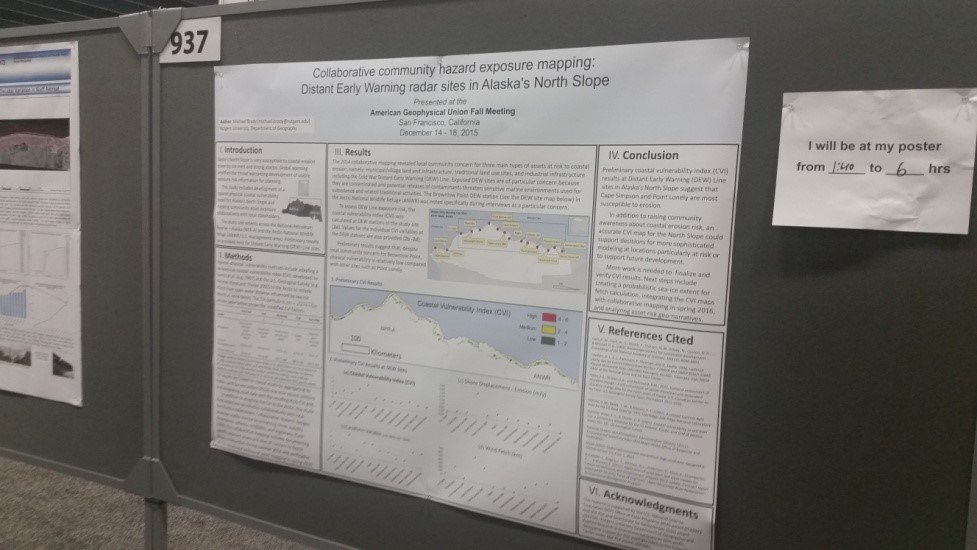

Originally known as the Rutgers Climate Institute Student Support Fund, this initiative was created in 2015 with a generous seed grant to the Rutgers Climate Institute from the family of William H. Greenberg (Rutgers University Class of 1944) to support Rutgers student travel and related expenses for the purposes of climate change education and research. With the Fall 2023 creation of Rutgers Climate and Energy Institute (RCEI), the Rutgers Student Support Program transitioned to RCEI.

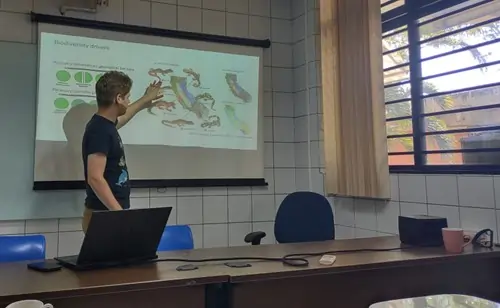

The RCEI Student Support Program is intended to further students' education and scholarship, enable them to develop, conduct and collaborate with other academics, and improve their ability to translate their research to a range of constituencies (e.g., general public, other students, educators, policymakers, governmental and non-governmental organizations) all key to their training as the next generation of climate and energy scientists, educators, and professionals. In addition, the Student Support Program facilitates students' ability to showcase their research, network and establish connections that will contribute to their success once they have completed their education at Rutgers University.

Awardees

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2025

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2025

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2025

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2025

Ph.D Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2025

Ph.D Candidate, Civil and Environmental Engineering

Travel Year: 2024

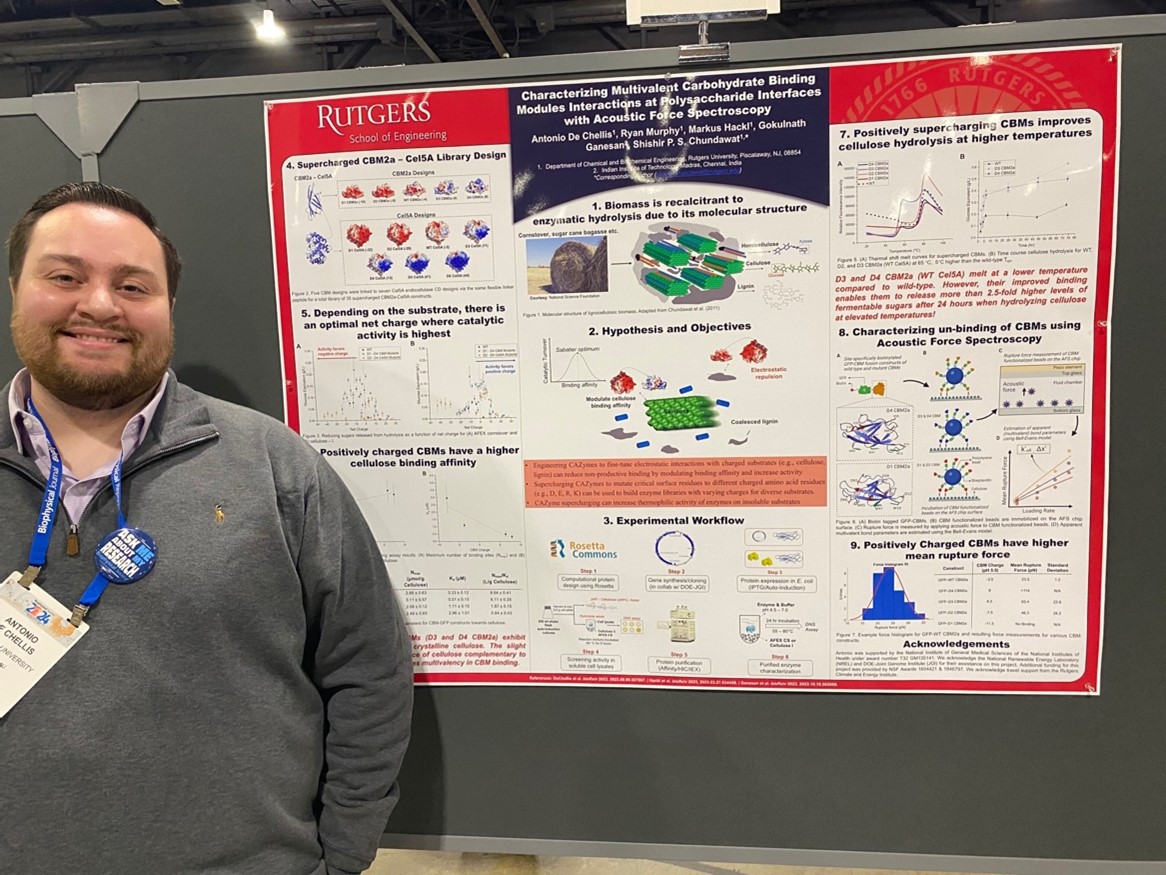

Ph.D Candidate, Biochemical Engineering

Travel Year: 2024

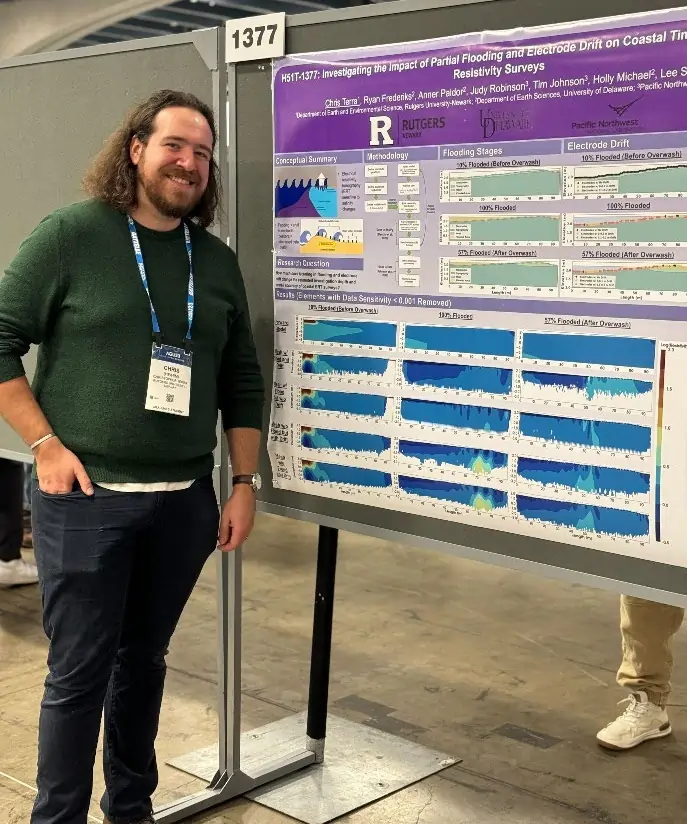

Ph.D Candidate, Earth and Environmental Sciences

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Earth and Environmental Sciences

Travel Year: 2024

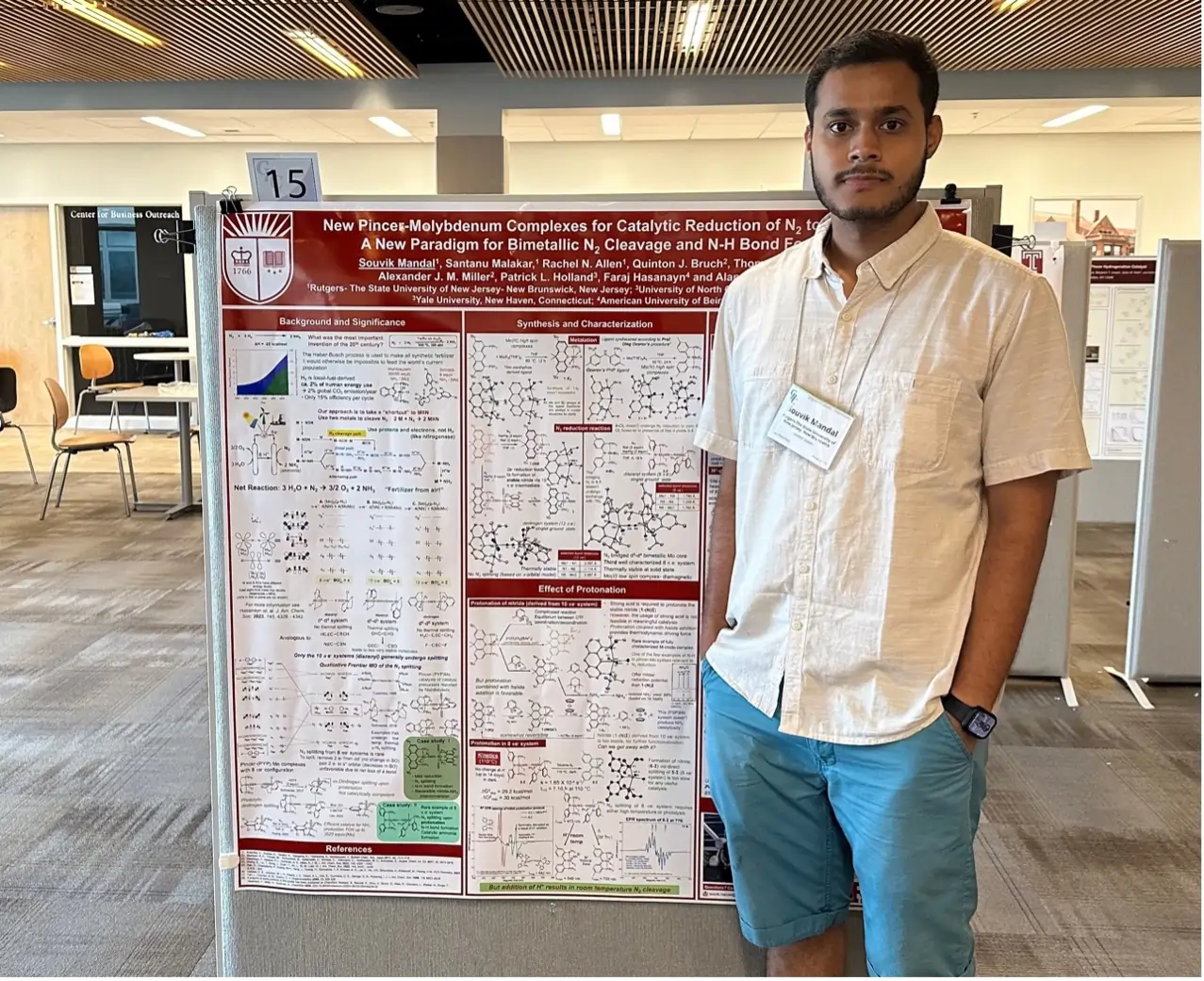

Ph.D Candidate, Chemistry

Travel Year: 2024

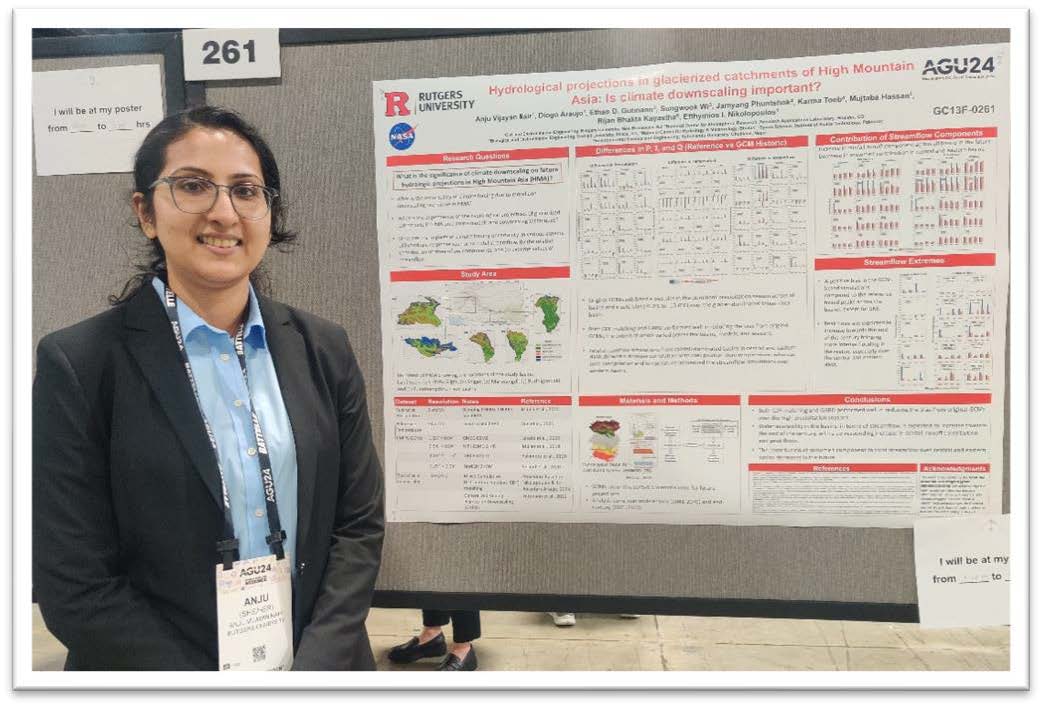

Ph.D Candidate, Civil and Environmental Engineering

Travel Year: 2024

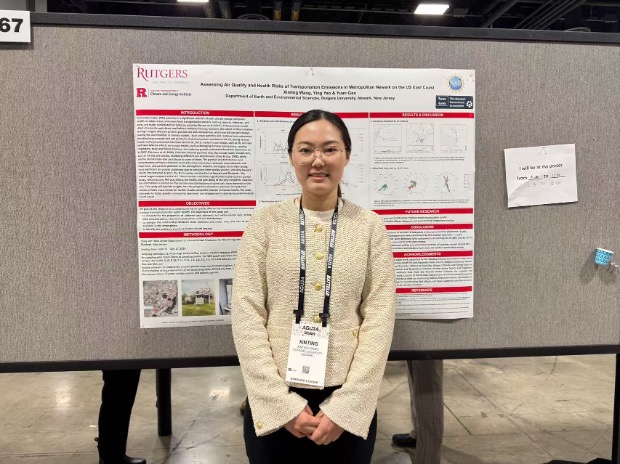

Ph.D Candidate, Earth and Environmental Science (Newark)

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Microbiology

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Earth and Environmental Science (Newark)

Travel Year: 2024

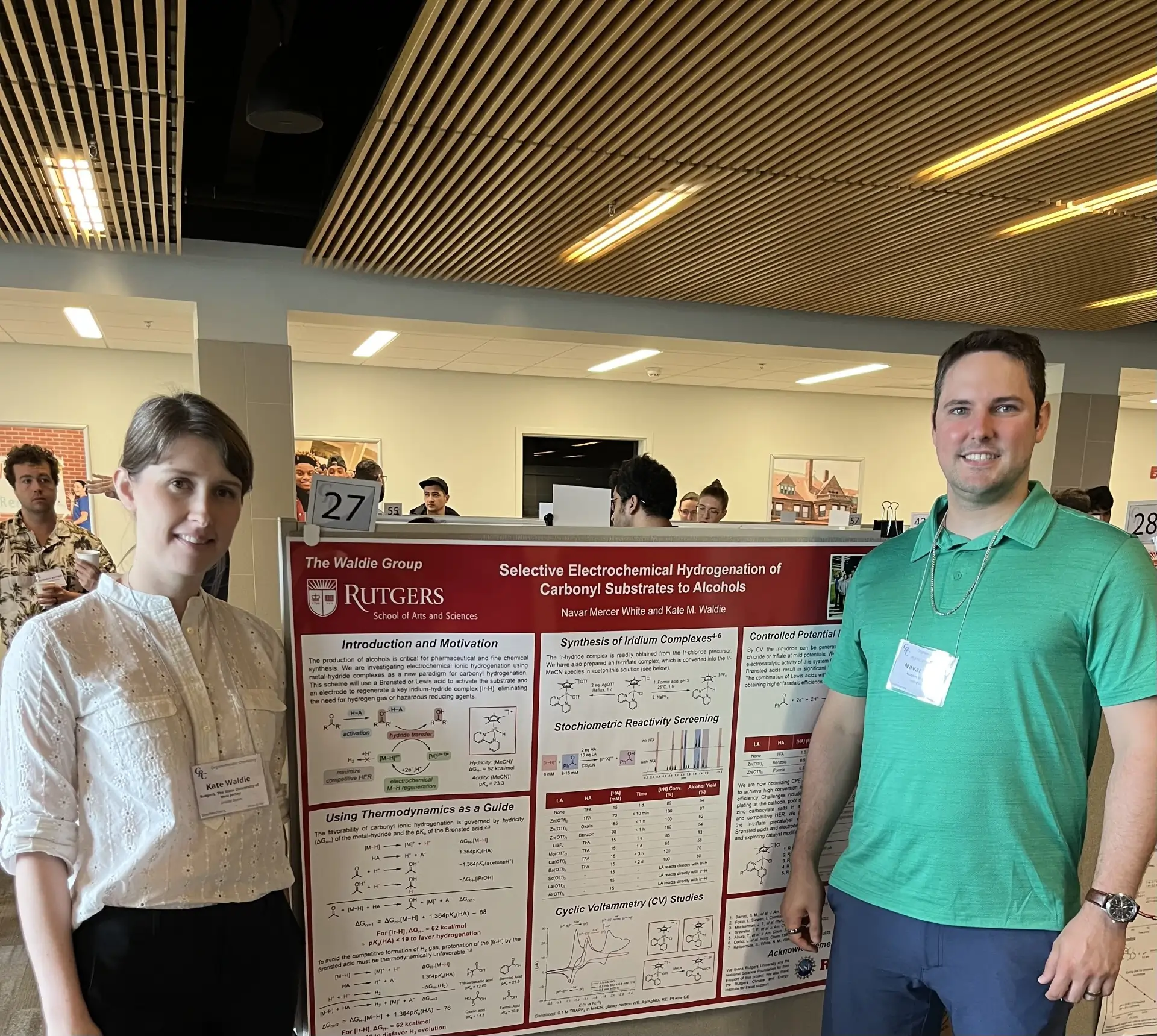

Ph.D Candidate, Chemistry and Chemical Biology

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Bloustein School of Planning & Public Policy

Travel Year: 2024

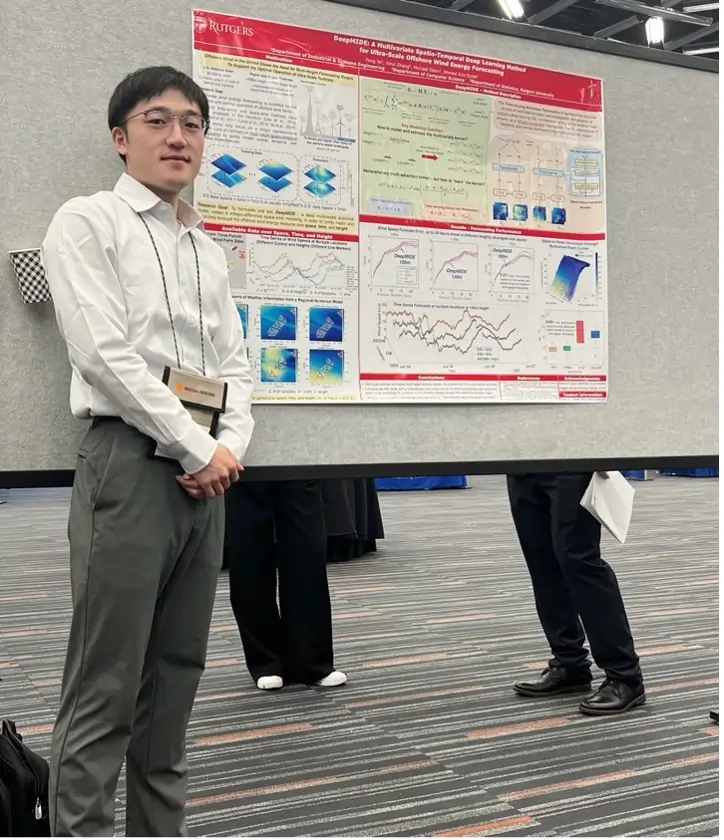

Ph.D Candidate, Industrial and Systems Engineering

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D Candidate, Industrial and Systems Engineering

Travel Year: 2024

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Global Affairs, Rutgers Newark

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D Candidate, Geography

Travel Years: 2023, 2022

Ph.D. Candidate, Ecology, Evolution, & Natural Resources

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Plant Biology

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2023

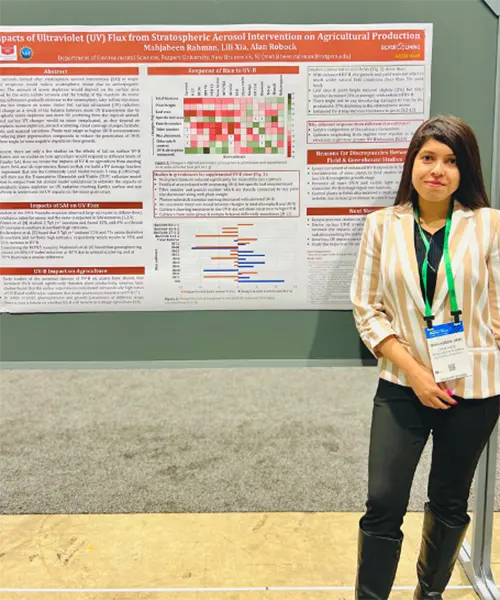

Ph.D Candidate, Atmospheric Science

Travel Year: 2023, 2022

Ph.D Candidate, Ecology & Evolution

Travel Year: 2023

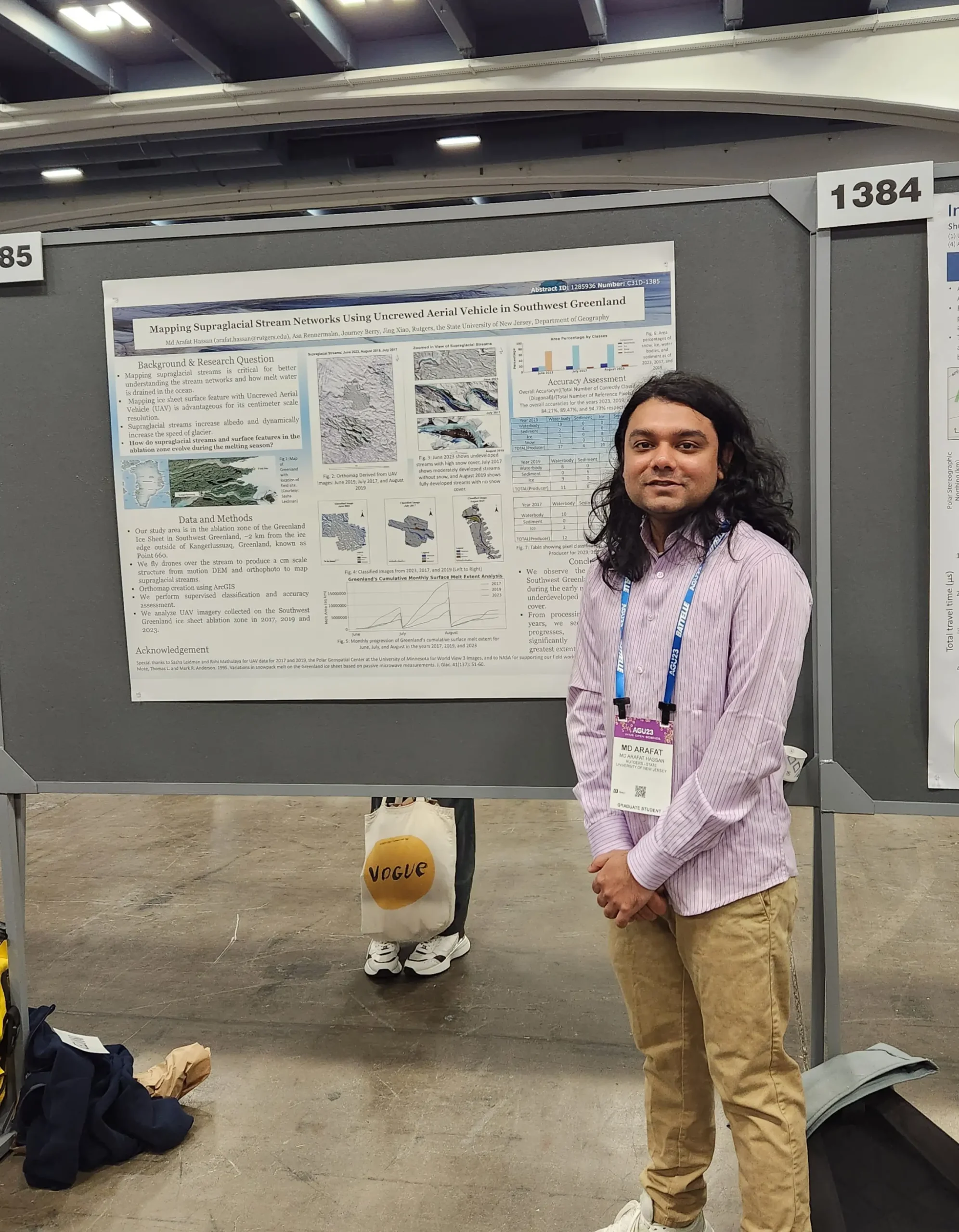

Ph.D Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Ecology, Evolution, & Natural Resources

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Anthropology

Travel Year: 2023

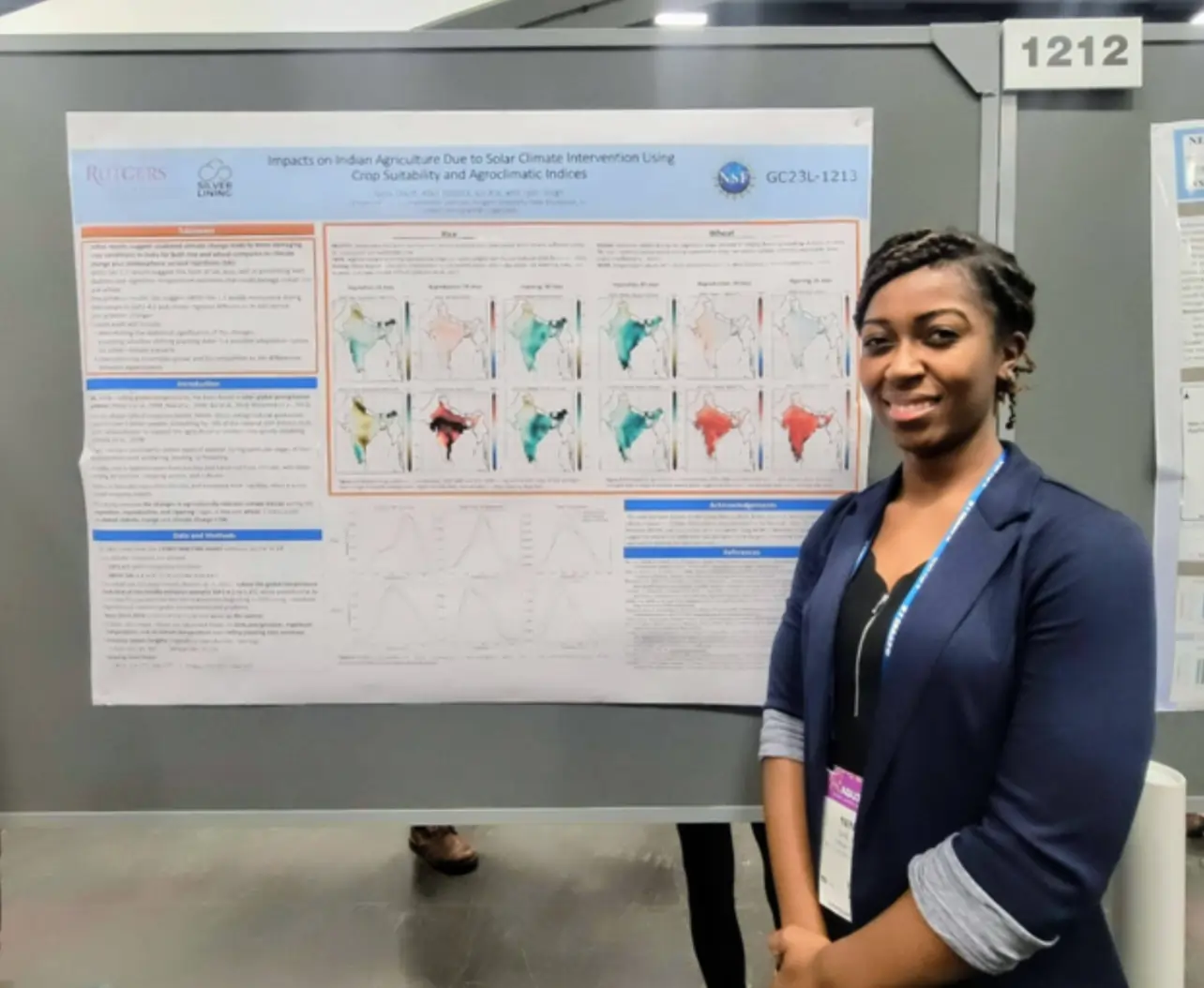

Ph.D. Candidate, Environmental Science

Travel Years: 2023, 2022

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Sociology

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Atmospheric Science

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D Candidate, Earth & Environmental Science

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D Candidate, Earth & Environmental Science

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Ecology, Evolution, & Natural Resources

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Sociology

Travel Year: 2023

Ph.D. Candidate, Education with a concentration in Theory, Organization and Policy

Travel Year: 2022

Ph.D Candidate, Environmental Sciences

Travel Year: 2022

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceangraphy

Travel Year: 2022

Ph.D. Candidate, Environmental Geology, Rutgers Newark

Travel Year: 2022

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2022

Ph.D. Candidate, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning & Public Policy

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning & Public Policy

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2016

Ph.D. Candidate, Atmospheric Sciences

Travel Year: 2016

Ph.D. Candidate, Ecology, Evolution, & Natural Resources

Travel Year: 2016

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2016

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning & Public Policy

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Oceanography

Travel Year: 2015

Ph.D. Candidate, Atmospheric Sciences

Travel Year: 2017

Ph.D. Candidate, Geography

Travel Year: 2015