- This event has passed.

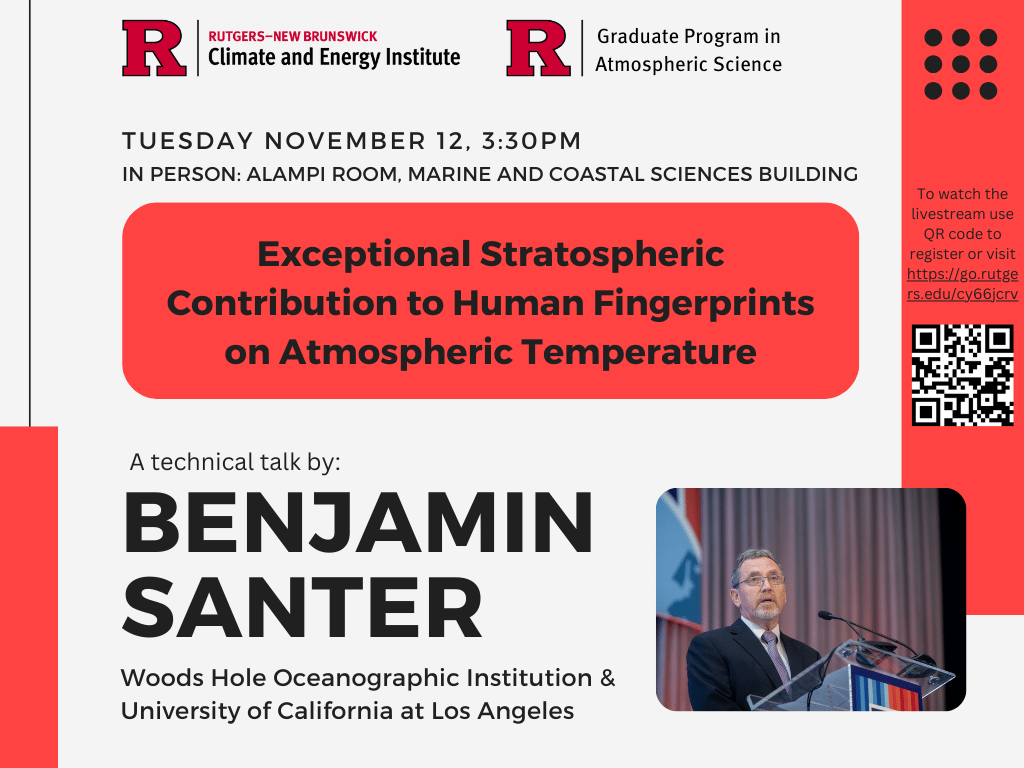

Exceptional Stratospheric Contribution to Human Fingerprints on Atmospheric Temperature

Benjamin Santer will give a technical talk titled “Exceptional Stratospheric Contribution to Human Fingerprints on Atmospheric Temperature”. The talk is hybrid and will take place on Nov. 12, 2024, at 3:30 PM in the Alampi Room, Marine and Coastal Sciences Building and Webinar through Zoom, with this registration link. This event is co-sponsored by RCEI and Rutgers Graduate Program in Atmosperic Sciences. Below is Dr. Santer’s description for the talk:

In 1967, Suki Manabe and Richard Wetherald used a simple climate model to predict that human-caused increases in atmospheric CO2 should warm Earth’s troposphere and cool the stratosphere. This important signature of anthropogenic climate change was subsequently documented in weather balloon and satellite temperature measurements extending from near-surface to the lower stratosphere. Stratospheric cooling has also been confirmed in the mid- to upper stratosphere, a layer extending from roughly 25 to 50 km above Earth’s surface (S25-50). Until recently, however, S25-50 temperatures had not been used in pattern-based attribution studies of anthropogenic climate change.

My talk describes the first such “fingerprint” study, with satellite-derived patterns of temperature change extending from the lower troposphere to the upper stratosphere. Including S25-50 information increases signal-to-noise ratios by a factor of five, markedly enhancing fingerprint detectability. Key features of this global-scale human fingerprint include stratospheric cooling and tropospheric warming at all latitudes, with stratospheric cooling amplifying with height. In contrast, the dominant modes of internal variability in S25-50 have smaller-scale temperature changes and lack uniform sign. These pronounced spatial differences between the S25-50 signal and noise patterns are accompanied by large cooling of the S25-50 layer (1-2°C over 1986 to 2022) and low S25-50 noise levels. Our results explain why extending “vertical fingerprinting” to the mid- to upper stratosphere yields incontrovertible evidence of human effects on the thermal structure of Earth’s atmosphere.

The end of my talk will consider a simple thought experiment: If satellite temperature data had existed in 1860, when could a human fingerprint on atmospheric temperature have been first detected? I will address this question with output from CMIP6 simulations of historical climate change.